Protecting Something Sacred

By Katy Heggen on March 28, 2018 in Blog

Photo courtesy of Effigy Mounds National Monument

Photo courtesy of Effigy Mounds National Monument

In 2013, the Iowa Department of Transportation (IDOT) was preparing to expand US 20 in Woodbury County when a team of archaeologists came across something they hadn’t anticipated —geoglyphs.

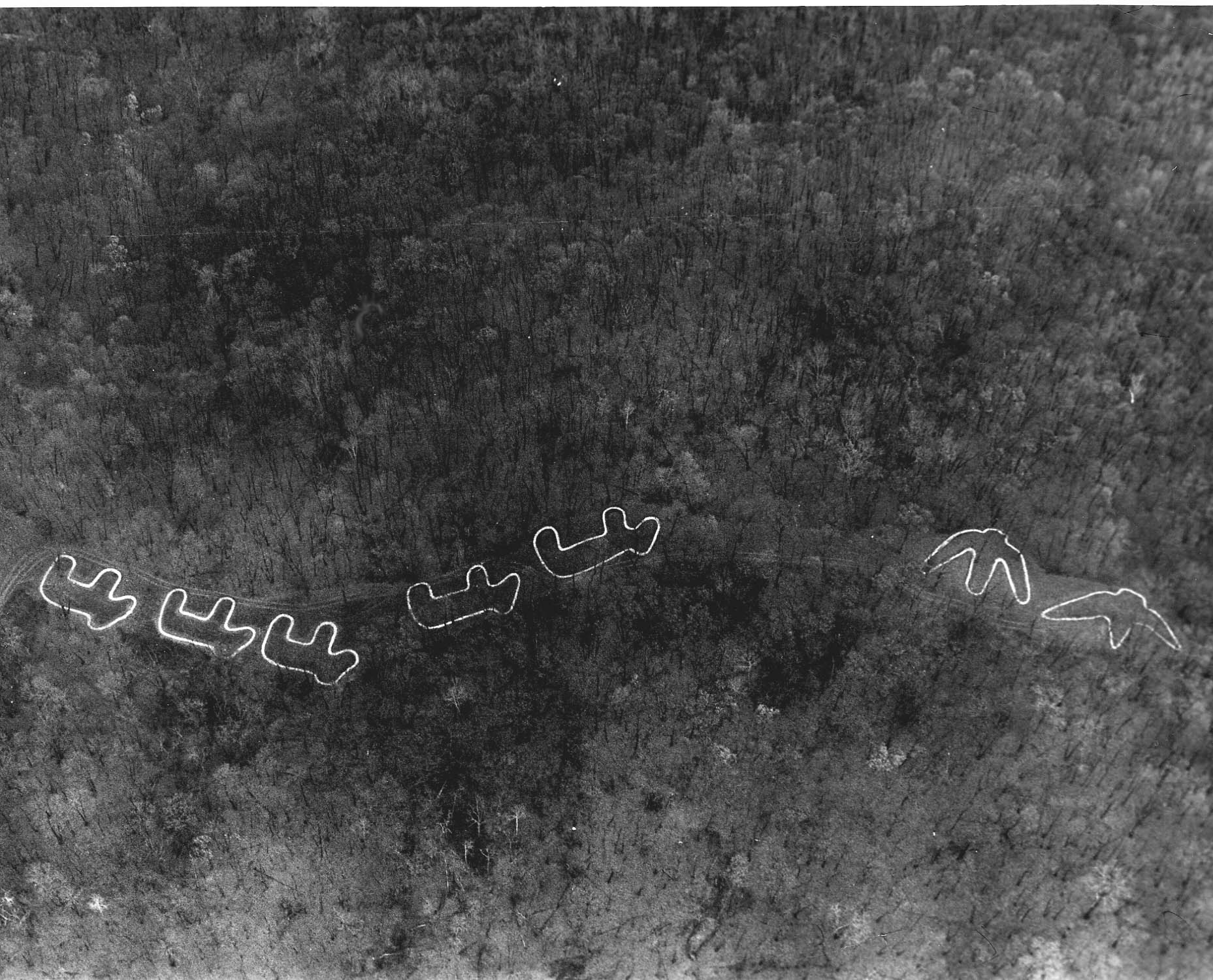

Geoglyphs are human-made designs etched into the ground. They vary in size, construction and subject, and are often best appreciated from an aerial perspective. Among the geoglyphs rediscovered in western Iowa was an effigy of a bison measuring approximately 50 feet from head to tail. With both above and below ground components, the geoglyphs in Woodbury County are unique, and the first of their kind to be rediscovered in the state.

“Although we don’t know for sure what the people who made these shapes intended, we know that their location on the landscape is as important as the symbols,” said Tribal Historic Preservation Officer Lance Foster, Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska, who was featured in Lands that Shape Us, a video IDOT created about the project.

The Loess Hills and surrounding area have been home to several Native American tribes throughout history, including the Omaha, Ponca, Ioway, Dakota and Sioux tribes, among others. Woodbury County is especially rich in Native American sites of historic, cultural and spiritual significance.

Preserving the past, protecting the future

While state and federal law provides protections for some kinds of Native American sites — burial grounds, for example — others are open to interpretation. Modern land protection plays an important role in safeguarding these special places.

“The vast majority of land in Iowa is privately owned,” said State Archaeologist John Doershuk, who oversees the Office of the State Archaeologist at the University of Iowa. “One of the best ways to permanently protect these sites — on public and private land — is conservation easements. The past is a nonrenewable resource. If we’re going to learn anything from it, we need to preserve it. We all benefit from being good stewards of these lands.”

Beyond conservation easements, public protection of such places can also safeguard their important cultural and natural resources. In 2017, INHF purchased 90 acres of woodland in Woodbury County. The land — characterized by stunning valleys, slopes and deep deposits of loess soil — will be part of a larger complex of protected land in the area that includes the rediscovered geoglyphs.

Like fragile habitats, some Native American land features are better left alone, out of respect for their cultural significance or to avoid causing damage to the site. As such, while the Office of the State Archaeologist maintains a database of archaeological sites, information about sensitive native sites is not public.

“We were not told the exact location of the geoglyphs they found, but they are either on property adjacent to our purchase or on this and other adjacent lands,” said recently retired WCCB Director Rick Schneider. “We have great interest in helping protect and preserve these sites.”

The land will be open to the public and managed by Woodbury County Conservation once fundraising for the project is complete.

Native American mounds and other historic markers of pre-European settlement life can be found across Iowa. These “earth works” are often huge in scale — sometimes unrecognizable from plain view. Photo by Clint Farlinger

Common ground

While the earth works found in Woodbury County were unique, the presence of Native American land features on properties INHF has helped protect and preserve is not.

Native American sites including burial grounds, spiritual sites and villages can be found across the state. These places — and the surrounding lands — still hold significant meaning for native communities not only in Iowa, but across the Midwest and beyond.

“There are twenty-six tribes we currently work with that have an interest in and connection to Iowa,” said Doershuk. “Many of those tribes don’t live here anymore, but still feel that this is their historical homeland and that the features found here are an active part of their culture today.”

“For us, everything is in a circle,” said Tribal Historic Preservation Officer Samantha Odegard, Upper Sioux Community. “It’s not just a place, it’s part of who we are. It’s all connected. The more we know about the site, the more we know about our history, culture and spirituality. The more we know about those things, the more we know ourselves.”

Many of these lands also hold great natural value.

“If you think about the areas that native communities inhabited, they’re usually in beautiful spots located in strategic positions near waterways, on high points, etc.,” said INHF Senior Land Conservation Director Heather Jobst.

INHF has worked to protect areas of Native American significance many times. Effigy Mounds National Monument in Allamakee County, Kuehn Conservation Area in Dallas County, O’Brien County’s Waterman Prairie and INHF’s Heritage Valley in Allamakee County are all areas protected by INHF that are home to Native American features and importance.

“These places are universally found to be beautiful and significant, and are often areas we would be protecting even if those Native American features weren’t there,” said Jobst. “The fact that they are makes the project all the more important.”

Collaboration is key

How these lands are protected and managed and in consultation with whom is as important as what is being protected and why.

“It comes down to listening to us,” said Odegard. “We provide the best information we can, but sometimes all we can say is ‘it needs to be protected.’ It’s hard to take those things on faith, but there are reasons for those things.”

IDOT and the Federal Highway Administration consulted with several Native American sovereign nations on the US 20 expansion — as required by state and federal law — both before and after the Woodbury County geoglyphs were discovered.

“My role at IDOT is heavily focused on consultation efforts,” said Brennan Dolan, a cultural resource manager and archaeologist at IDOT, who worked on the US 20 project. “I do a lot of site visits, interact with tribes, other archaeologists, public officials and others to share project information and make sure we’re not impacting something we shouldn’t be impacting. Consultation is a collaborative process.”

“Whether you’re a state agency like IDOT, land trust or private landowner, if you own property of any magnitude, by default, you’re a cultural resources manager,” said Dolan. “We have a responsibility to say ‘we have a resource of cultural significance, who should we talk to?’”

.jpg)

Prairie Awakening is held each year at Kuehn Conservation Area in Dallas County. The area has significance to local and historic Native American tribes, and the event celebrates the human connection to the Iowa landscape. Photos courtesy of Chris Adkins, Dallas County

Meaningful interpretations

Like protection, interpretation on Native American land features is most meaningful when informed by the descendants of those whose history, culture and beliefs it seeks to interpret.

Prairie Awakening is an annual event featuring Native American song, dance and storytelling held each fall at Kuehn Conservation Area in Dallas County, which is home to several Native American sites.

“We created this idea that we’re going to awaken the prairie, and as we awaken that, we ourselves will reawaken our connections to the land,” said Chris Adkins, an environmental education coordinator and naturalist with the Dallas County Conservation Board (DCCB).

Prairie Awakening began when Adkins and his colleagues traveled to native communities around the Midwest, inviting tribal elders to return to Iowa be a part of Prairie Awakening. They were led by Maria (Running Moccasins) Pearson, an Ames-based activist and leader in the passage of landmark state and federal legislation that provided protections for Native American human remains and their repatriation.

Robert Knuth and Irma White have been instrumental in Prairie Awakening since its beginning nearly 20 years ago. Both were close friends of Pearson, who passed away in 2003, and have served on state advisory committees focused on Native American affairs.

For them, Prairie Awakening is a way of creating a greater understanding, appreciation and respect for these places and the people, culture and values that are part of it.

“It’s a living history,” said White, a member of the Omaha and Winnebago tribes of Nebraska. “It’s a way of teaching, sharing knowledge and passing it on to the next generation.”

It’s also a way to connect people to the land and their effect on it.

“When you’re part of something and understand it, you don’t desecrate it,” said Knuth, a member of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate. “You begin to realize that the effect is like a stone in the water, the ripples go out.”

Shaped by the land

Adkins often asks people to close their eyes and picture the wildest place they’ve ever been. He’s heard all kinds of responses over the years, but there’s one feature rarely included in the descriptions: people.

“Humans are part of this landscape, not separate from it,” said Adkins. “Often times, when we think about the places we gravitate to, there’s something about that place helps us connect and remember. Until we start viewing ourselves as part of that place, we’ll never re-inhabit that place or part of ourselves.”

These significant places are worth protecting, for many different people and reasons. We all play a part in the history of these wild areas — and hopefully can find and re-root ourselves in the strong sense of place.