Nature's Puzzle

By District Forester Joe Herring on January 16, 2024 in Blog

“So then what does a forester do in the winter time? You know, when the leaves are all gone and you can’t identify the trees?”

I remember being surprised the first time someone asked me this question. Winter, after all, is really the best time to be in the woods observing and taking inventory of the trees, identifying issues and maintenance needs and ultimately conducting management prescriptions such as thinning or harvesting. Like a heavy fog that has lifted, the winter forest scene provides 20/20 vision after the dense summer foliage has given way.

In order to “see the forest for the trees” during the dormant season, it does take some botanical teaching and practice. Winter tree identification commonly combines observations of bark color and texture; twig patterns and leaf scars; the size, color and shape of buds; attached fruit, nuts, leaves, or seeds; and overall size and shape of the tree. It’s no surprise that most people don’t venture further than the green summer leaves of maples or oaks when learning about tree identification.

But for the hardy adventurer, a winter hike or snowshoe through an Iowa forest can be a magical and rejuvenating experience. Learning to identify even just one or two of the most common trees that you encounter, as well as their ecological connections to the wildlife and other parts of the forest, will make the experience so much richer. For example, once you learn that those wicked thorns on the Honey Locust evolved as a way to protect them from grazing mastodons and other megafauna of the Pleistocene, you will continue on your snowy journey with a little more appreciation for that tree species’ natural adaptations.

Here, I’ll shine a light on a few of the key characteristics of some of my favorite trees in winter.

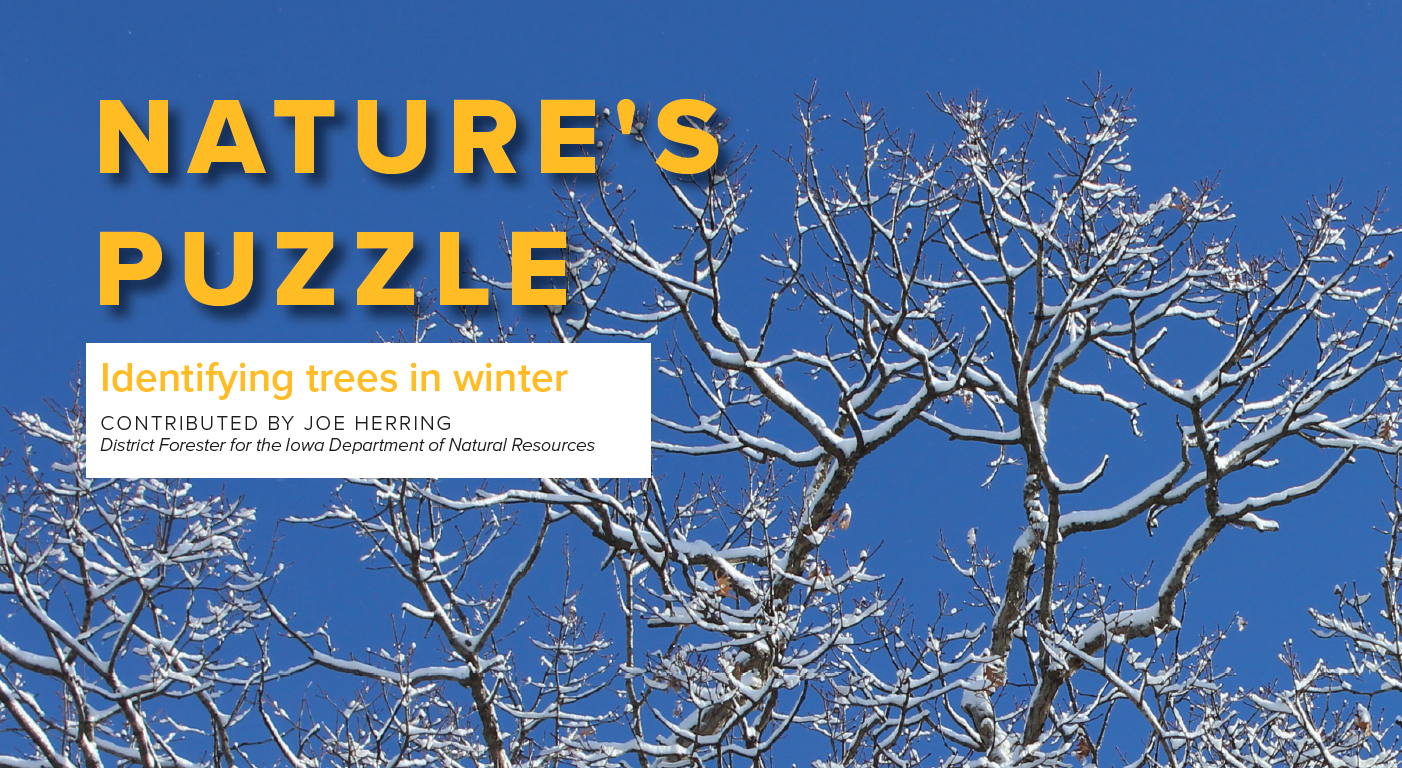

1. Swamp white oak (Quercus bicolor)

1. Swamp white oak (Quercus bicolor)

These trees are becoming more common in our urban areas, and I could not be happier about that. They are an excellent all-around shade tree. In winter, look for orange leaves that are still attached all the way until spring. The leaves are diamond-shaped and have very shallow, serrated lobes like the teeth of a saw. The upper branches have “exfoliating” bark that peels off and reveals green color beneath. Most of these trees will be small or medium in size because they’ve only become popular to plant in the past thirty years or so. They tend to have very straight, vertical trunks compared to other oak species.

2. Hackberry (Celtis occidentalis)

Unbeknownst to many but extremely common, Hackberry is a very easy tree to learn due to its unique “warty” or corky bark. Hackberry can be easily found in most forests as well as along streets and neighborhoods. The small berries, which are pea-sized and purple, often stay attached long into winter and provide food for Northern Cardinals, Northern Flickers and other birds.

3. Linden/Basswood (Tilia americana)

Basswood tends to be found in older, mature woodlands as it is a shade-tolerant, late-successional tree. Here, they are often found growing in clumps of multiple stems. But this beautiful shade tree can also be found planted along city streets or in yards. A key identifying characteristic is the bud, which is nearly globe-shaped, smooth and distinctively bright red in color. The bark on young trees is light gray and smooth (and is usually rubbed by deer), but on older trees will be shallowly furrowed with long, narrow, parallel ridges.

4. Bitternut hickory (Carya cordiformis)

Unlike its more commonly known shagbark companion, this widespread hickory has very smooth, tight bark. Its most unique trait is its bright yellow, mustard-colored buds. The trunk is nearly always very straight and vertical, and often will have noticeable concentric “rings” encircling it at higher points. These are an interesting response of the tree to the systematic horizontal pecking of Yellow-bellied Sapsuckers, a type of woodpecker.

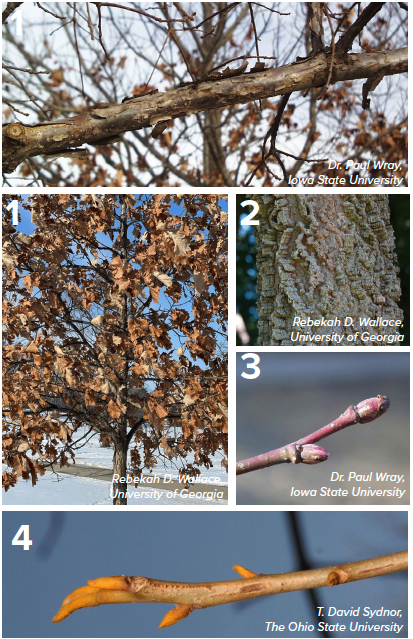

5. Eastern white pine (Pinus strobus)

Our only native pine tree found naturally in northeast Iowa, the beautiful white pine has been planted all across the state in windbreaks, cemeteries and cities. Besides the dark green and very soft, flimsy needles, the best way to make a positive identification is that its needles come in bundles of five. Most other pines planted in Iowa (Jack, Red, Scots) will have needles bundled in groups of two. Its narrow, 8-to-10-inch cones are also unique to white pine.

6. Ironwood (Ostrya virginiana)

These small or medium trees are found widely across the state growing in the shady understory of many mature uplands. A key winter ID feature is the orange-brown leaves that remain attached through most of the winter—once your eye becomes trained to this, you’ll see ironwoods everywhere! The bark on mature trees develops very narrow, long rectangular strands that can be shaggy and peel off with a gentle rub.

7. American bladdernut (Staphylea trifolia)

This native shrub occurs sporadically in mature forests across the state but would be hard to identify if not for its unique seed pods. After its clusters of bell-shaped white flowers have completed their cycle in the spring, air-filled seed capsules with three distinct papery compartments are borne and remain attached well into the winter. The shrubs can form thickets or colonies that are often found near tributary streams, but also sometimes on upland sites. Winter twigs are reddish or greenish brown with white stripes and have buds directly opposite of one another.

8. Black cherry (Prunus serotina)

Many people don’t know just how widespread and common our native wild cherry is. Growing tall, its trunk is dark black in color and older trees sport scaly, textured bark reminiscent of corn flakes cereal. Young trees and twigs are smooth, gray and have many white spots called lenticels. The leaves and flowers of the cherry and its shrubby relatives (chokecherry, pin cherry, and plum) are all very important for pollinators and caterpillars.

9. Elderberry (Sambucus canadensis)

This is another common shrub found across the state in floodplain forests, wet riparian zones and brushy ditches. In winter, elderberry stands out for its white colored stems and twigs with prominent bumpy lenticels. The twigs and buds attach in “V”s opposite one another. In late winter you’ll often see heavy deer browse on the twigs of this shrub.

10. Honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos)

Found prominently in forests that used to be pastured, this tree is known for its conspicuous woody thorns and 8-12-inch-long flattened leathery seed pods that can hang on late into winter. The bark of older trees is very dark colored and often has long upturned ridges. However, not all trees bear seed pods (there are separate female vs. male trees); and, some specimens do not have any thorns, a genetic variant known as Gleditsia triacanthos var. “inermis”, a latin word meaning “unarmed.”

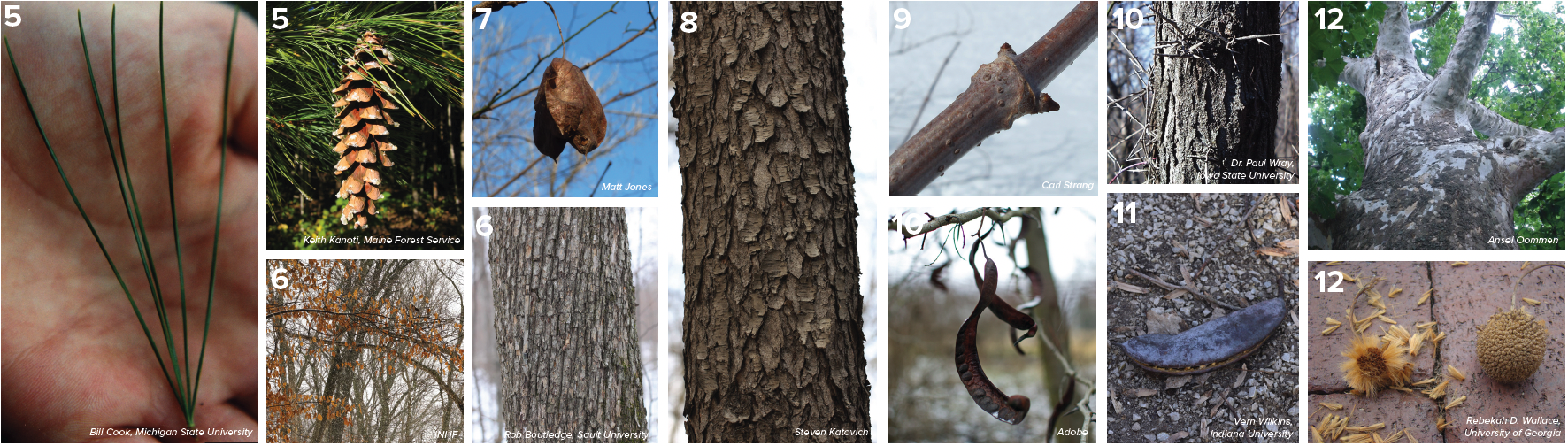

11. Kentucky coffee tree (Gymnocladus dioicus)

An increasingly common tree to use for urban plantings, this legume also has unique bean pods like its relative the honey locust; however, the pods on this species are much shorter and fatter at 4-6 inches long and are more football shaped. Note that there are male trees and seedless cultivars which would not bear pods. The other standout trait of the coffee tree in winter is the combination of its scaly bark coupled with an austere crown of stout, thick and crooked branches.

12. American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis)

The mighty sycamore stands out as a giant, attaining some of the largest heights, trunk diameters and leaf sizes of any native tree. Distinctive chalky white bark on the upper branches and trunk is exposed behind peeling layers of brownish bark, while golf ball-sized seed balls hang from the tree like ornaments all winter. You can find this tree generally in the southern half of Iowa along streams and rivers, but it and the hybridized London Planetree variety are sometimes planted in urban spaces, too.

Identifying trees and shrubs in winter is a challenging but fun skill to learn. Attending a forestry field day or just spending time hiking with a knowledgeable botanist, forester, naturalist or gardener is a great way to start learning. For more information on winter or year-round tree identification, check out Forest and Shade Trees of Iowa (Third Ed.) by Van der Linden and Farrar, or the Iowa State University Forestry Extension webpage. For history-minded plant lovers, the Iowa State College Extension Circular 246 by J.M. Aikman and Ada Hayden (1938) is a fascinating document, with original twig drawings by Dr. Hayden.