Remnant Prairie: A closer look at Iowa's rarest landscape

By Katy Heggen on August 24, 2017 in Blog

Heather Jobst has seen her fair share of remnant prairies — more than most. But every time she steps onto one, the effect is still the same.

“There’s something magical about being at those places,” said Jobst, INHF senior land conservation director. “You start thinking about how long it’s been there, about the history of that place. Remnant prairies have a way of bringing us back, of reminding us where we are.”

By simple definition, remnant prairie is true native prairie. Unlike restored or reconstructed prairies, which have been reestablished or returned to prairie, prairie remnants are fragments of the original, pre-settlement prairie landscape.

“First and foremost, it’s a piece that has not been greatly disturbed and has maintained some of its original vegetation,” said Dr. Daryl Smith, founder and former director of the Tallgrass Prairie Center. “The quality of remnants varies considerably, but when I think of remnant prairies, I think of prairies that have remained relatively intact.”

Historically, prairie once covered 75 to 80 percent of Iowa’s landscape. Now, less than 0.1 percent of that original prairie remains, scattered throughout small pockets across the state.

Iowa's changed landscape

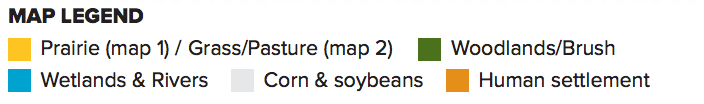

Below is a comparison of historic and modern land cover in Iowa. It’s estimated that 80 percent of the state was once covered by prairie, the largest percentage in the nation. Today, less than one-tenth of one percent of Iowa’s native prairie remains, mostly existing in small, untouched parcels. Maps by INHF

1830s-1850s (original land survey)

.jpg)

2009

.jpg)

“Native prairie is overwhelmingly rare in Iowa,” said INHF President Joe McGovern. “We must do everything we can to preserve this important part of our natural history that is so fundamental to our future.”

The Loess Hills contain the largest amount of prairie remnants remaining in Iowa. Pristine native prairies can also be found in the rolling hills of southern and south central Iowa, the prairie pothole region of northern Iowa, and the blufflands of eastern Iowa.

“Remnant prairies tend to be found in areas where the landscape was too steep, rocky or wet to farm,” said John Pearson, an ecologist with the Iowa DNR. “Of course, there are exceptions to those extremes.”

At 240 acres, Hayden Prairie State Preserve in Howard County — a favorite of both Pearson and Smith — is the largest prairie remnant in Iowa outside the Loess Hills. Bursting with an incredible array of wildflowers, prairie grasses and an abundance of wildlife, this public prairie preserve offers an amazing glimpse into Iowa’s prairie past. While the size of Hayden Prairie is unique — remnant prairies in Iowa tend to be small and isolated — the diversity found there is not.

“The ecological diversity in any remnant prairie — regardless of size — is noticeably different,” said INHF Land Stewardship Director Ryan Schmidt. “You see it in the soils, plants and animals. Nowhere else in the state can you find that level of diversity; it’s got it all.”

At minimum, remnant prairies are home to approximately 100 species of prairie plants — some with roots known to reach depths of 20 feet. High quality prairie remnants can contain in excess of 300 species of prairie plants. In contrast, a reconstructed prairie can have between 20–100 plant species. Remnants also provide critical habitat for a wide variety of threatened and endangered wildlife including large and small mammals, birds, pollinators, reptiles and insects.

That diversity, which has developed over thousands of years, is also incredibly difficult to recreate. Soil conditions, micro climate and the sheer volume of species that manage to coexist are unique to remnants. Native seed can be incredibly difficult to collect due to size — some as small as 100,000 seeds per ounce — and availability, and many varieties are difficult to germinate and grow.

“Prairies are amazingly complex,” Schmidt said. “These ecological communities have been together for so long — the interactions happening within that ecosystem are unbelievable. Remnants are both the model and measurement for success in prairie restoration and reconstruction, but they’re impossible to replicate.”

While remnant prairies occupy a small percentage of Iowa land, the benefits they offer to the larger landscape extend far beyond their own acreage. In addition to providing wildlife habitat, remnants slow and filter water, protect soil health, offer open space and cultural value. They also provide access to native prairie seed, which can be collected to support and expand prairie research and restoration projects.

The scarcity of remnant prairie, coupled with the inherent challenges in and opportunities for prairie restoration, make these beautiful lands a high protection priority for INHF. Prairies may no longer dominate Iowa’s landscape, but their roots run deep, and the remnants that remain are persistent.

“When you consider everything we’ve done to alter the landscape of Iowa and you find a prairie that has persevered, you can’t help but think that there has to be a lot of resiliency in that,” said Jobst.

Explore Iowa's Remnants

Here’s a look at some of our favorite remnant prairies in Iowa.

Doolittle Prairie State Preserve

Located in Story County, Doolittle Prairie is a 40-acre expanse of pothole prairie rich in prairie wildflowers and grasses. The property is divided into two tracts, the northern tract, which is owned and managed by the Iowa DNR and Story County Conservation Board, and the southern tract, owned by Story County Conservation Board, which was purchased with the help of INHF.

Turin Prairie

A short one-hour drive from Council Bluffs or Sioux City, Turin Prairie encompasses 467 acres, including 200 acres of high quality native prairie, in the heart of the Loess Hills. Nearly 1,000 people contributed to help INHF and partners permanently protect this pristine prairie.

Bernau Prairie

In 2010, Bernau Prairie in Kossuth County was the largest known unprotected native “black soil” prairie left in Iowa, measuring 125 acres. It gained permanent protection through INHF conservation easements in 2011.