Prairie Perspectives

By Erica Place on May 22, 2023 in Blog

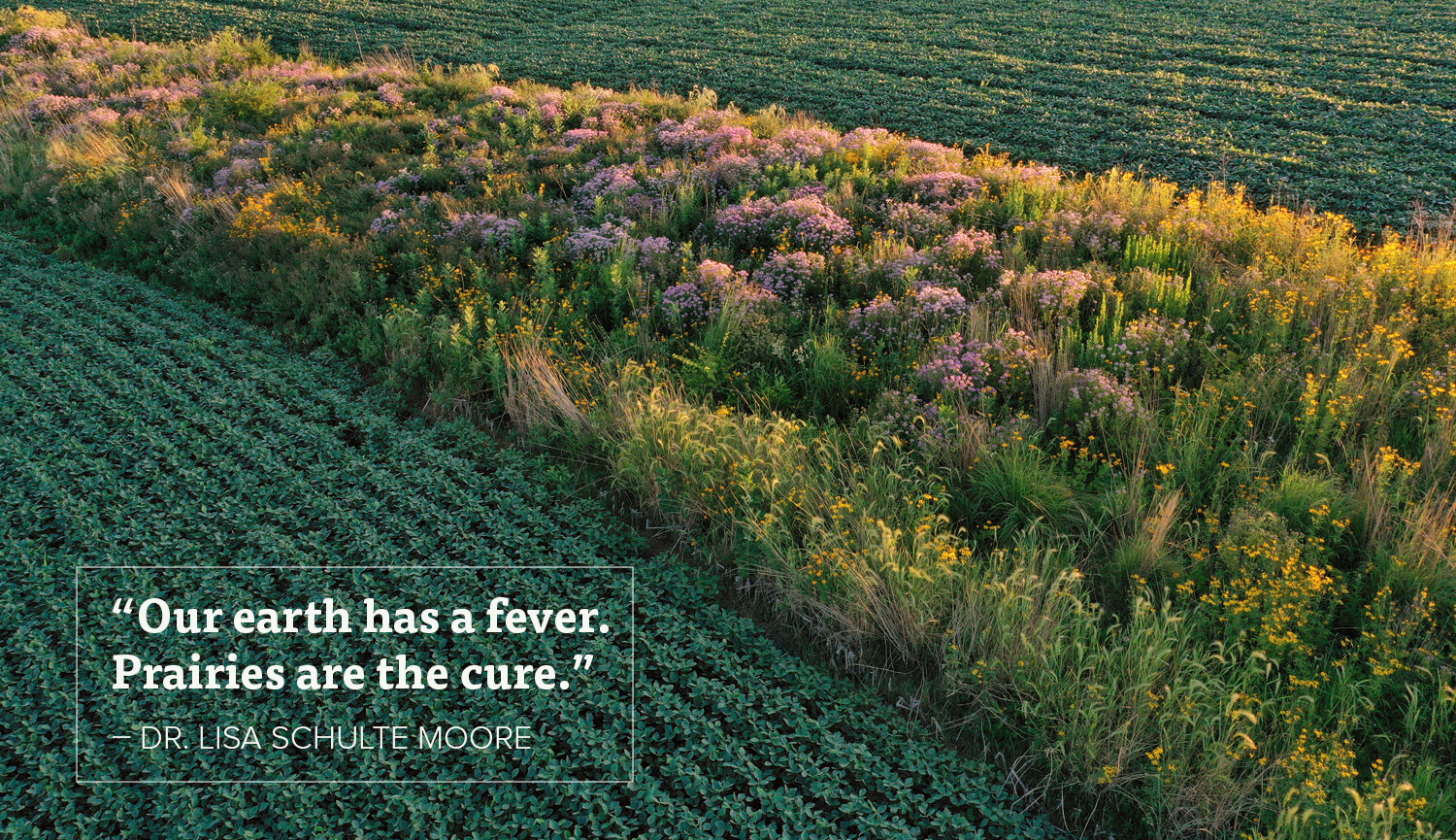

Photo by Omar de Kok Mercado/Iowa State University STRIPS Project

When you hear the words “old-growth forest,” an image likely forms in your mind. Trees larger around than a hug and much taller than a two-story, the bark painted with multicolored lichens. An undisturbed ecosystem, with all its visible and underground connections still intact. A relict existing through pivotal points in history, standing by while the constitution was signed or the first automobile was built. We’re inherently protective of old-growth forests; they feel special. So why, when we’re instead talking about original prairies that have most certainly outlived the trees, do we not also think in terms of old-growth?

A forest is generally deemed “old-growth” if it meets a handful of criteria: it developed over a long period of time safeguarded from substantial disturbance; it has a complex structure and rare or unique plant communities; and it usually has minimal issues with invasive species. These same concepts characterize a prairie remnant.

Twelve to fourteen-thousand years ago, after the last glaciers receded from Iowa, our blank slate of a state began to transform into a grassy ecosystem. The grasses and flowers that took root and the wildlife that grew to depend on them for food and cover persisted for the thousands of years that followed. While many aspects of Iowa prairie changed following Euro-American settlement, what has survived — remnants — are artifacts of this ancient landscape. Looking at a prairie remnant is a bit like stepping back in time. Their structure, composition and relationships are ancient, just as in an old-growth forest.

Some of the individual plants are ancient, too. Well-adapted to minor above-ground disturbance like fire or grazing, the bulk of the prairie lives below the surface of the soil. While many forbs are relatively short-lived, there’s evidence that bunch grasses have the potential to live for millennia. Blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis), mostly found in Iowa in the Loess Hills, can live for 450 years. That’s older than Iowa’s oldest known white oak.

While the individual microbes and organisms themselves lead brief lives, the undisturbed soil structure of a prairie remnant is a well-oiled machine, and we know that Iowa’s fertile soils are owed to the breakdown of thousands of years’ worth of organic material from prairie vegetation and roots.

In short, the soil is important. Dr. Mahdi Al-Kaisi, professor emeritus at Iowa State University and creator of Iowa Learning Farms, spent his career as a soil scientist. Aside from physical properties like porosity or mineral content, Al-Kaisi explains that the living components — bacteria, fungi, nematodes, etc. — are just as critical to soil health.

“Imagine the microbial community is the engine that drives the car,” Al-Kaisi said. “Without the engine, you lack richness in the soil makeup.”

Microbes are a huge component of how nature cleans water, how nutrients cycle, how carbon is stored. They’re mighty machines! Many of our modern agriculture practices like tillage throw this engine off-balance. Again, just as with old-growth forests, the system is healthiest when void of substantial disturbance.

The prairie’s biodiversity — both above and below ground — brought strength to the landscape, making it resilient to changes and warding off invasive species. Prairie held hundreds of plant species, each appearing in something else’s life cycle as a host or source of food or shelter. The connections between these living things are intricate, and we likely only understand a fraction of the symbiotic relationships fine-tuned over time.

Some of those relationships still exist; bottle and cream gentian (Gentiana andrewsii and Gentiana alba) rely almost exclusively on bumble bees for pollination, reserving their nectar only for the insects strong enough to open their closed petals. Other pieces of the prairie web of life are on the verge of being lost, like plains pocket gophers or Franklin’s ground squirrels — both critical in cycling nutrients and creating habitat — but now on Iowa’s Species of Greatest Conservation Need list. Or — in the case of bison, wolves or prairie chickens — the pieces are already lost, their absence having a palpable ripple effect. Even our highest quality remnant prairies, the best examples of what Iowa once was, can no longer be considered fully intact.

Some of those relationships still exist; bottle and cream gentian (Gentiana andrewsii and Gentiana alba) rely almost exclusively on bumble bees for pollination, reserving their nectar only for the insects strong enough to open their closed petals. Other pieces of the prairie web of life are on the verge of being lost, like plains pocket gophers or Franklin’s ground squirrels — both critical in cycling nutrients and creating habitat — but now on Iowa’s Species of Greatest Conservation Need list. Or — in the case of bison, wolves or prairie chickens — the pieces are already lost, their absence having a palpable ripple effect. Even our highest quality remnant prairies, the best examples of what Iowa once was, can no longer be considered fully intact.

The fragmented nature of what remains is a problem, too. Some species continue to vanish from our state simply because there’s not enough prairie left. A study done by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology in 2019 revealed that North American grassland bird populations have declined 53% since 1970. Henslow’s Sparrows (Ammodramus henslowii), once common throughout the Midwest, are one of those grassland bird species in steep decline over the last half-century. Its preferred habitat is at least 250 contiguous acres of moderately tall, dense grassland vegetation with thick litter, free of woody encroachment or the commotion of heavy grazing. In other words, this bird needs large, diverse old-growth prairies.

Over thirty million acres of prairie once covered this state. It is estimated that less than 0.1% of that remains. Most of our old-growth prairies are lost to the ages. What exactly have we sacrificed? Can we put it back?

One study done by Al-Kaisi and his graduate student at the time, Jose Guzman, examined how soil function differed between cultivated sites, prairie reconstructions and prairie remnants. The cultivated site and reconstructions were located within Neal Smith National Wildlife Refuge in Jasper County, and the remnant at nearby Rolling Thunder Prairie in Warren County, both properties INHF helped to protect. Al-Kaisi looked primarily at the differences between stored and sequestered carbon and microbial biomass between these sites, finding that not only was the remnant holding the most carbon and boasting the highest microbial biomass, but was able to demonstrate through modeling that it may take more than 100 years for a reconstructed prairie to function as well as (or close to) a remnant by those measures.

Even with the best planting and management plan, a good prairie reconstruction still takes time to establish… maybe even more than previously thought. Indicator species, or plants that are sensitive to environmental degradation but are essential to overall biodiversity and health and function of the ecosystem, don’t readily establish even under ideal conditions. An article published in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment explains that “…old-growth grassland communities require many decades, and probably several centuries, to assemble.” And it goes without saying that there are challenges associated with putting large mammals like bison or wolves back on the landscape to help make the picture more complete.

But truly, there’s not a lot of research that articulates exactly what is gone and how hard it would be to replicate it. Remnant grasslands and their soils are understudied and there’s just not the funding to support the needed basic science investigations. Yet, nearly everyone we talk to who holds prairie near and dear has this innate understanding that the remnants are special. They are old-growth. And we’ve got to do what we can to protect what we still have, and do our best to restore or reconstruct it where we can.

Dr. Lisa Schulte Moore, professor in the Department of Natural Resource Ecology and Management at Iowa State University and a 2021 MacArthur Foundation Fellow, has been studying what prairie reconstructions can do even on a modest scale. She’s the co-founder of the Science-based Trials of Rowcrops Integrated with Prairie Strips (STRIPS) project, which integrates small amounts of prairie in strategic locations in agricultural fields. “Reconstructed prairies, once established, can help hold soil and nutrients in place, can help cycle carbon and water, and can provide habitat for a broad suite but not all native prairie-adapted species,” Schulte Moore explained.

Dr. Lisa Schulte Moore, professor in the Department of Natural Resource Ecology and Management at Iowa State University and a 2021 MacArthur Foundation Fellow, has been studying what prairie reconstructions can do even on a modest scale. She’s the co-founder of the Science-based Trials of Rowcrops Integrated with Prairie Strips (STRIPS) project, which integrates small amounts of prairie in strategic locations in agricultural fields. “Reconstructed prairies, once established, can help hold soil and nutrients in place, can help cycle carbon and water, and can provide habitat for a broad suite but not all native prairie-adapted species,” Schulte Moore explained.

Her team’s research shows that by converting 10% of a crop-field to diverse, native perennial vegetation, farmers and landowners can reduce sediment movement off their field by 95 percent, and total phosphorous and nitrogen loss through runoff by 77 and 70 percent, respectively. If that little bit of prairie can do that much good, just imagine the impact of a 100-acre chunk here or there.

INHF’s Conservation Programs Coordinator Emily Martin has been helping guide the creation of the Iowa Climate Assessment, an in-depth analysis of Iowa’s past and potential future climate using the best available science. As work continues on this collaborative document slated for completion next year, it’s clear that prairies need to be a part of our long range vision.

“Carbon dioxide is 79 percent of the United States’ greenhouse gas emissions, and in 2021 made up 66 percent of Iowa’s,” said Martin. “There are many different approaches we must take across all industries to reduce our emissions to meet our national goal of a 50 percent reduction in carbon emissions by 2030. Restoring our natural ecosystems, especially prairie, has a significant role to play. We can put carbon back into the soil through prairie plants, but to do that, we need to let the land rest. Iowa is in a unique position to show the power of prairie in helping to solve the climate crisis — both by mitigating emissions and lessening impacts, like flooding. Iowa’s soils are what make this state; we need to tend to them now before we lose in the span of 150 years what took thousands of years to build.”

Al-Kaisi echoes the sentiment, citing that “prairie is more effective than trees or row crops in capturing and storing carbon. It is important to think about any opportunity to convert any piece of land [back to prairie]. It’s a good investment. The multiplier is unlimited for climate benefits, wildlife habitat, aesthetic value or any other measure.”

In a matter of 70 years, we disassembled something we can never really replace. But we can get close, and we have to try. For more reasons than nostalgia. “Our earth has a fever,” Schulte Moore said. “Prairies are the cure.”