The bedrock beauty of Whitewater Canyon

Posted on June 20, 2016 in Blog

by Jean C. Prior

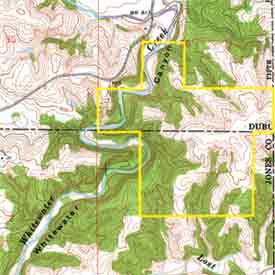

The word “canyon” is rare among Iowa place names. But there it is, on a U.S. Geological Survey topographic map, identifying a deep, twisting, forested segment of Whitewater Creek.

As the creek flows from southern Dubuque County into northeastern Jones County, its valley abruptly narrows to a constricted gorge bound by steep bedrock bluffs, a series of sharp turns and tight meander loops deeply entrenched into the surrounding landscape: Whitewater Canyon. The zig-zag course takes nearly three miles to cover a two-mile, straight-line distance. Below the canyon, the creek valley broadens again before emptying into the North Fork of the Maquoketa River.

Looking out across the rolling countryside from Highway 151 or county roads, you could miss this canyon all together. Only on near-approach does the sudden, 150-foot drop into this geological gem come into full, spectacular view.

In addition to great scenery, this canyon offers lessons in Iowa geology, both here and throughout the state.

Rock solid foundations

Rock solid foundations

Such eye-catching features in Iowa’s scenery are usually the result of underlying geological conditions. The landscape-changing factor in this case is bedrock: durable dolomite—a magnesium-rich limestone.

This rock formation, which lies much deeper under central and southwest Iowa, was deposited as limey mud and shell fragments in a warm, clear, shallow sea that covered the interior of North America about 430 million years ago (Silurian age). In fact, the exposed bedrock contains many marine fossils.

Though this bedrock is most exposed in the canyon itself, you can catch glimpses of it nearby: in weathered rock knobs poking through to the land surface, in layered strata exposed along road cuts and in local stone quarries. The usual mantle of glacial-age clays and silts that masks Iowa’s bedrock elsewhere across the state is quite thin here. Upstream, Whitewater Creek and its tributaries have occasional brief contacts with bedrock, but nowhere more dramatically than in beautifully carved Whitewater Canyon.

Forces & fractures

Looking into the canyon from blufftop overlooks, one’s eye is drawn to its straight, sheer walls of rock and to the winding course of both creek and valley below.

The bold bluffs actually follow fractures, or planes of weakness, through the bedrock. These developed earlier in the region’s geologic history when rigid bedrock masses fractured under long-term stress associated with regional warping of the Earth’s crust. The resulting vertical fractures, called “joints,” tend to occur in parallel sets and at nearly right angles to each other.

Whitewater Creek, taking the path of least resistance through the dolomite, follows first one fracture trace and then another, often with right-angle turns. This erosion pattern is repeated in deep vertical crevices that open behind and parallel to major cliff faces, in tributary ravines entering the canyon at nearly right angles, in rectangular bedrock “chimneys” standing apart along the bluffs, and in angular blocks of bedrock lodged on the canyon’s lower slopes. State preserves and parks—such as White Pine Hollow, Backbone, Maquoketa Caves and Palisades-Kepler—are other places where Silurian bedrock produces dramatic effects on both topography and drainage patterns.

In addition to these pronounced vertical features, visitors will notice prominent horizontal ledges, overhangs and recesses. These occur along “bedding planes” that reflect the sedimentary rock’s original accumulation on an ancient sea floor. These layers, accentuated by differences in their resistance to erosion, provide picturesque relief to the rock faces as well as convenient footholds for vegetation.

Water power

Though highly resistant to erosion, dolomite is a carbonate rock, which makes it subject to the dissolving action of groundwater. Its porous, weathered surface is marked by small irregular cavities and pits called “vugs.”

Larger openings, even caves, can develop from chemical reactions to percolating groundwater—as well as by mechanical slippage of bedrock slabs to form angular openings along fracture traces. Such “karst” features—which also can include sinkholes, springs and algific slopes—are strongly associated with these Silurian rocks in eastern Iowa. Occasional groundwater seeps within the canyon are a reminder that these rocks also compose the Silurian aquifer, a major source of drinking water for eastern Iowans.

Common ground

Geology and ecology form a strong partnership in today’s canyon environment. The rugged landscape has isolated the valley from much disturbance. It hosts an array of natural habitats and ecological niches, reflecting the various geologic substrates, slope aspects and moisture conditions that are present.

Small prairie glades and gnarled cedars thrive along exposed bluff tops. Harebells and lichens cling to sheer bedrock walls. Canada yews and ferns line moist rocky recesses. Mosses coat the rock rubble at the base of cliffs. Oaks and hickories thrive in the upland forests and tributary ravines. Cottonwoods and bluebells grow amid bottomland deposits of sand and gravel along the creek channel and within the floodplain corridor.

Whitewater Canyon is a valuable natural and scientific asset, worthy of further inventory and interpretation by geologists, botanists, biologists and archaeologists. The canyon also preserves for future generations some fascinating and instructive geological chapters in our state’s natural history.

Additional resources:

Mycountyparks.com offers visitor information for Whitewater Canyon. Resources are available under Dubuque, Jackson and Jones counties. Learn park hours, recreational activities, features and history.

Jean C. Prior. Landforms of Iowa. University of Iowa Press, 1991. This full-color, readable account of Iowa’s landscape features describes their diversity across the state, their underlying earth materials, and the geologic processes responsible for their formation. Abundant photos, maps, diagrams, references, and places to visit.

Wayne I. Anderson. Iowa’s Geological Past: Three Billion Years of Change. University of Iowa Press, 1998. This books offers a comprehensive look at Iowa’s fascinating geologic past as preserved in its rock record, from ancient volcanic lavas to tropical seas teeming with marine life to massive ice sheets. Numerous photos, maps, diagrams and references.

Iowa Geological Survey website. This site contains a wealth of information, including a huge variety of maps and satellite images, educational materials, and a “browse area” with links to dozens of diverse topics ranging from the geology of specific state parks to Iowa’s statewide land cover inventory to “the age of dinosaurs in Iowa.”