The Last Link

By Erica Place on July 24, 2023 in Blog

Photo by Iris22 from RDG Planning and Design

Nearly all Iowa towns owe their location to a railroad. People gathered around amenities like fueling stations or train depots and rail service meant faster transportation of farmers’ crops and meat. Iowa’s rail network grew quickly, connecting communities to commerce. They linked everything together. Less than a century after construction first began, Iowa had more than 10,000 miles of railroad.

Railroad activity peaked by 1920 and trains fell out of favor as the main method of transportation of people and goods shifted to cars and roads. Deregulation in the 1980s caused many more rail lines to be discontinued, liquidated or abandoned. Less than half of those 10,000+ miles of track are still active today. But nearly 800 miles of former railroad corridors were saved and remain part of our transportation and recreation network. Constructed with gentle grades and sometimes following scenic rivers, they generally span 100 feet in width, preserving natural scenery on either side of a narrow path cleared wide enough for a train. Perfect, already existing infrastructure for future multi-use trails. Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation first began working on these conversion projects in the 1980s. Today, over 65% of Iowa’s rail-trails are former INHF projects, including some of Iowa’s most beloved multi-use trails.

The Raccoon River Valley Trail (RRVT) is a quintessential rail-trail conversion, making use of 89 miles of former railroad northwest of Des Moines. Trailside artwork, restaurants, lodging and other amenities have popped up along the route since it first opened in 1989. Today, RRVT is touted as the longest paved loop trail in the nation, joins 14 central Iowa communities across four counties and sees around 350,000 visits every year.

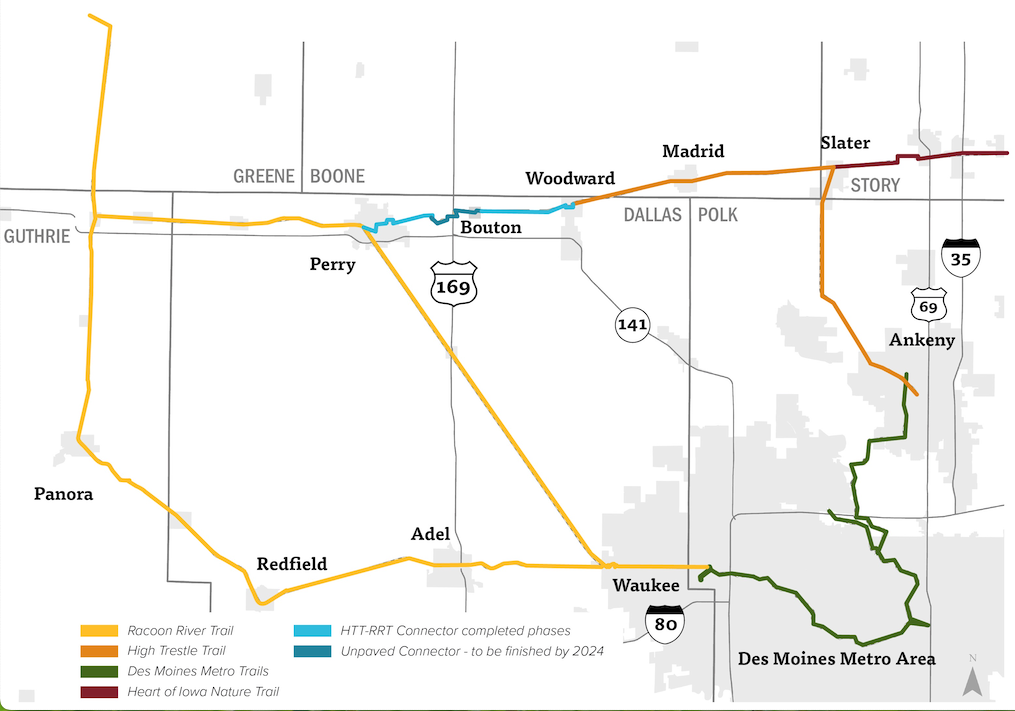

Nine miles to the east sits another notable rail-trail: the High Trestle Trail. Internationally -known for its half-mile, 13-story bridge over the Des Moines River — one of the largest trail bridges in the country — the High Trestle Trail attracts everyone from walkers and cyclists to bird watchers and those who just want to see the lighted bridge at night. It spans 25 miles and joins five towns across four counties, breathing new life into rural communities since it opened in 2011.

Business boomed in the years following the debuts of these regional trails as new visitors began to arrive. Communities suddenly had a bigger audience, and drew trail users in with new restaurants, pubs or bike shops.

Chelsea Johnsen, a Madrid restaurant owner, has seen the impact firsthand. Though there were many reasons Madrid felt right for their business, Sisters in Cheese, Johnsen says there’s no question the High Trestle Trail swayed their decision in favor of setting up shop in this small rural community. Harnessing the power of active trail users’ word of mouth advertising, they’ve filled their menu with health-conscious options and collaborated on trail-centered community events like this summer’s High Trestle Trail Fest.

“I grew up here and I’ve always had love for my hometown, but there were a few years when there just wasn’t much happening. When the trail opened, you could see sparks of that once-vibrant community coming back. Because of the trail, lots of the businesses that have been around for decades are thriving and new businesses are showing interest in opening their doors in Madrid. It’s given our community a lot of hope and we’re very grateful that it’s in our back yard. ”

Each of these rail-trails continues to impact transportation and generate economic diversity long after trains last ran down their tracks. They paved the way for new businesses that help small towns thrive. They connect people to nature, and one community to the next… imagine what would be possible if these two trail powerhouses were also connected to each other?

“When I started in 2006, we were helping to build the High Trestle Trail up to what it is now. Even back then, people were asking the question of when we were going to connect this to the Raccoon River Valley Trail,” remembers Andrea Boulton, INHF’s Trails and Community Conservation Director. “The desire for this connector does not come by surprise because trails are a community asset. They should be accessible and engaging for the folks that live there and be used as a tool for economic development and attracting people to your community.”

A nine-mile connector trail running between Perry and Woodward and through the town of Bouton would close the gap. Just like with the Raccoon River Valley Trail and the High Trestle Trail, an existing, former railroad corridor seemed a logical path forward for the trail alignment. But unlike other rail-trail projects, the corridor had long ago been parceled and sold to individual landowners, meaning all the needed pieces would have to be secured one by one. Though there was little hesitation in the value and need for this trail, there were plenty of questions about how everything would fall into place.

“You never know how long a project like this will take until you get going with it,” remembers Dallas County Conservation Board Director Mike Wallace. “As with many large trail projects it is a marathon, not a sprint!”

It is precisely for projects like these that INHF exists; budget limitations and timing constraints of years-long projects are often hurdles that public agencies can’t overcome, making them less nimble to respond when opportunities to protect natural areas or create new trails come knocking. INHF agreed to assist in securing the connecting pieces, and planning formally began in 2016 when Dallas County Conservation Board stepped forward as the future trail owner and manager.

Wallace contacted landowners along the desired route, explaining the vision for and potential impact of the connector trail. It took time to have all those discussions. Since each section was only useful if it had adjoining sections on either side, it made good sense to use option contracts — essentially putting each piece on hold until the entire route came into view. Every landowner’s willingness would be critical.

Holly Lester and Michelle Meier, whose father had purchased land with a section of the abandoned railbed in 1993, were excited when their family was among those approached about the trail project. “Mom was all about conservation, caring for natural habitat, and caring for the future of her community,” said Holly. Seeing this as an opportunity to give back to community and conservation, they agreed to sell a few acres of their family farm for trail development.

“We are excited to contribute to those efforts, even if just a small piece in the entire development of the trail. We are proud to be a part of providing bicyclists and trail users a chance to experience parts of Iowa from a different perspective.”

Through many similar conversations, the route was ultimately pieced together over the course of six years and via 17 individual parcels: 14 purchases, one bargain sale, one land donation and one easement donation. It followed the old railroad bed in most cases, but not all. Without any one of these pieces, the trail may have never been finished.

Identifying and securing the route was only part of the lift; funding was also needed for engineering and construction. A Federal Recreational Trail grant, State Recreational Trail grant, Resource Enhancement and Protection (REAP) grant, Destination Iowa grant and contributions from county and city budgets, local foundations and hundreds of trail supporters helped make this project’s nearly $8 million price tag a reality.

Having long been in the hearts and minds of many, the project is finally nearing completion with the roughly four remaining miles slated for construction between now and 2024. Coupled with existing trails in the Des Moines metro, the new connector (which is an extension of the High Trestle Trail by name) will create two loops — one 86 miles with a spur to Jefferson, and the other a massive 118 miles — moving people through communities and across the Iowa countryside.

The cities connected through this expanded trail system are sure to see the impact of increased outdoor recreation. Bouton’s population has been declining since the 1980s, on trend with other rural Iowa communities seeing an exodus to metros. Around 130 people currently call Bouton home. But situated almost exactly halfway between Perry and Madrid, Bouton is almost certain to become a trail user’s stopping point for lunch or leisure. And they’re ready.

“Bouton has been holding out hope for a recreational attraction for decades,” said a member of the Bouton Betterment Committee, a group dedicated to planning events and community improvements. “We’re ready to rally to support more visitors and make sure folks see Bouton as the caring small town it really is.”

Drifters, Bouton’s local pub, is also bracing for the increased tourism. Having only been the owner for about one year, Tara Klocke can recognize that the trail will bring opportunity.

Drifters, Bouton’s local pub, is also bracing for the increased tourism. Having only been the owner for about one year, Tara Klocke can recognize that the trail will bring opportunity.

“It feels like it’s putting Bouton on the map. It will be nice to see new people come through—they might travel from 60 miles away!”

The full impact could take years to realize, but the benefits of regional trails are well-proven. Just like the railroads that came before them, they provide economic opportunities and quality of life components. They’re a community’s invitation to visit and many residents’ reasons to stay. They offer connections to each other, to nature, to community and commerce. “The completion of this project connects a major gap in the central Iowa trails network,” said Wallace. “Thousands of people will benefit.”

With the transfer of the last connecting piece to Dallas County Conservation Board finalized in 2022, INHF’s role has concluded and we’re cheering them on to the finish line.