From Acorn to Oak Tree

By Joe Jayjack on December 9, 2019 in Blog

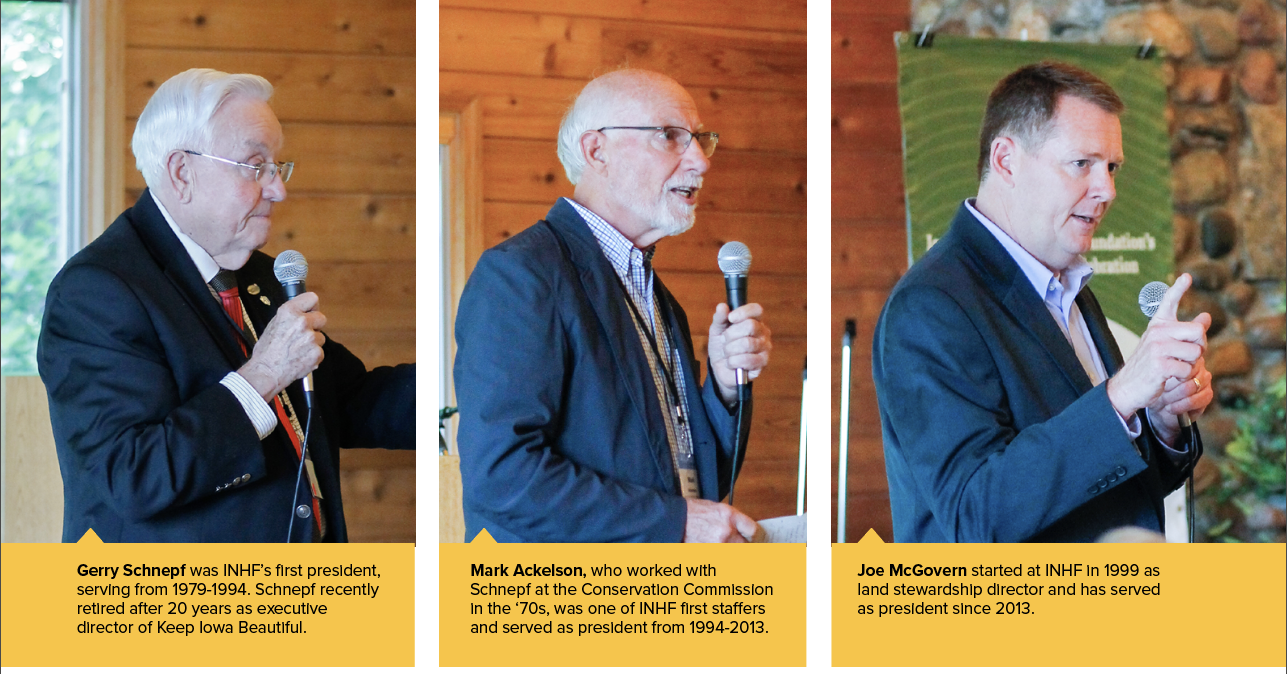

As Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation’s 40th anniversary year comes to a close, we look back on the early years of the organization through the eyes of the three people that have served as president of INHF: Gerry Schnepf, Mark Ackelson and Joe McGovern. This story was edited together from different interviews conducted over the past year.

Beginnings

Gerry Schnepf: I was with what was then called the Iowa Conservation Commission (now the Iowa DNR). I can’t tell you about the number of occasions we had as an agency trying to acquire property in which we were never timely enough, or responded quickly enough or in the right manner. Also, we were government and people didn’t want to deal with us.

Mark Ackelson: Gerry and I had been really frustrated about the lack of progress being made on conservation, recreation and wildlife issues in Iowa. It was obvious that there was a really important role for a private organization to do in concert with others, including the Conservation Commission, that which they couldn’t do on their own.

GS: As a result of that I went to the director of the Conservation Commmission at the time and I said “I’ve got an idea I’d like to try.” So we went in and visited with Gov. (Robert) Ray, and the governor said, “Well, who would be a good group of people to review an organization like this?” One was Bill Brenton of Brenton Banks. Another was Robert Buckmaster (president of KWWL-TV in Waterloo and INHF’s first board chair). He was an avid fly fisherman and hunter. Bob and I went and visited with Anna Meredith (of the Meredith Publishing family) about this new organization. We were at her home south of Grand Avenue in Des Moines and we’re sitting there talking and she says, “Do you hunt?” And Bob says, “Yeah, I hunt a lot, including turkey. And here’s what a turkey sounds like.” And he whips out a mouthpiece for a turkey call and starts calling turkeys. With that, and a lot of laughter, we knew we were on the right track.

Gov. Ray was provided a list of potential board members and helped to establish the initial board of directors, which had 12 members and Buckmaster as the chair. The board soon expanded to include more than 30 members from around the state. Today, the INHF board of directors has 34 members.

GS: The governor did something interesting at their first meeting. He had everybody around a big table and he asked, “I want each of you to tell me personally why you want to be involved.”

Joe McGovern: I think the board is the very heart and soul of our work. That tradition was established very early on, and you see it play out today. We do have a big board, and that’s where we get a lot of strength. We cover the state. Our staff and board work very well together.

GS: The initial slogan: “For those who follow.” When Bill Fultz (partner at CMF&Z and early INHF board member) was putting together the branding and everything, I went to him with two pages of options and he looks at it and turns it over and says, “Alright, let’s start over.” And he came up with it almost instantly. I’ll never forget that.

Land protection

MA: The first project was Whitham Woods in Fairfield. It was really quite interesting. Daisy Whitham was really concerned about the future of her property and she wanted to make it available to the public. She said, “Here’s what I want to do, and I’m not so sure I trust you, but I don’t have anybody else to do this.” And we did.

Whitham Woods is still owned by INHF and leased to Jefferson County Conservation Board. The former nursery is a popular spot for hiking, photography, fishing and bird watching.

JM: Our role is making sure that those places are available. We want to make sure that they are there forever. We strive to make sure that when we do something, it lasts. When I look back over the last 40 years and we can talk about our first project still being there, still being available to people, that is very important to me.

GS: The other side of the equation, our first big project, was the Mines of Spain in Dubuque. We ended up getting a grant from the Secretary of the Interior — $1.2 million.

MA: It was a really complex project. Our board knew about that. This kind of set the tone for how INHF was going to operate. We didn’t know where the money was going to come from. Complicated legal issues. And the board said, “Let’s test ourselves.” The board could have taken something really easy, but they wanted to tackle the difficult stuff right away. Then we got involved in two trail projects!

Trails

GS: The first one was from Waterloo to Cedar Rapids — The Cedar Valley Nature Trail. We worked with three donors: Dick Young, Bob Buckmaster and Carl Bluedorn. And those three put up all the money to acquire that right-of-way. There are what I call big-big people and big-small people. These were big-big people. They just did what was right and for the right reasons.

MA: Now it doesn’t sound like a lot of money, but in the early ‘80s we were talking about buying the right-of-way for $650,000, and there were no grant programs available for it. Again, that risk, how do we do this? There was more controversy than we had estimated.

GS: Pioneer Hi-Bred made a $200,000 commitment to the trail. But an adjacent landowner wanted the land. So he went to Pioneer and asked them to back off. So five of the top people from Pioneer met with Ann Fleming and four other INHF board members, and eventually, Ann says “You’re blackmailing us. You want us to give up on this idea for the state just because you don’t want to pay out that money and that landowner wants the land.” And she said, “Well, guess what? We’re sticking with it.” And I about had a heart attack. That was a hard swallow — losing the support of Pioneer. But eventually they came back. Boy, Ann was strong. That’s what I mean by big-big people.

MA: I was escorted out of town twice, at public meetings on two different trails, for my own safety by the sheriff. I remember being asked to appear before a board of supervisors about a proposed trail. And I went to the meeting and suddenly they set me up in the courtroom with my back to a huge audience of angry people. That’s unfortunate, but it was also part of the learning process. About how to prepare and engage the public.

GS: There was a clear role for INHF, because at that time the legislature restricted the DNR from getting involved in trail projects.

MA: The question I got a lot was “Why does INHF do trails? Isn’t INHF a conservation organization?” Well yeah, but part of getting people outside is having trails so they can do that. A lot of those original trails were also about habitat. Some of those trails are in parts of the state that, back then, was about the only habitat that was left was these old railroad corridors. A lot of these communities that we worked with on trails were originally tied together by the railroad. Then when the railroad was gone, relationships changed. As one of our volunteers said, “I never liked those people because the only time we saw them was on the football field on Friday night. And now I get to know them!”

JM: We’re clearly focused on nature. But we’re also focused on the relationships and the partnerships and how important it is that we all do this together. We can’t do this alone. We don’t want to do it alone. We want to make sure that everything is done in a way that raises all the boats. Because it will last a lot longer if we are doing this together.

GS: Another thing we did early on was Buckmaster, Duane Sand (INHF’s soil stwardship program consultant) and I made visits to national agriculture companies. At the time, the most popular images in farm publications to promote products was bare black soil. And it was because it was a good graphic contrast. So Duane analyzed all these major companies and their advertising. We flew all over the place to meet with these top CEOs, and we said, “We’re not going to ask you for money. We want you to do one thing: Change your photos.” And, by golly, in a year’s time they all changed. They all went to no-till and different kinds of operations. And that’s a very subtle thing, but I think it did a lot in leading to change.

Transitions

MA: I feel really honored to have been asked to be president of this organization (in 1994). I can’t imagine my career being anything more satisfying than what I was able to find here and help create. But it’s not all about the president, as you know, it’s about the whole organization, including the board, the volunteers, the donors, the staff and the landowners and communities we worked with.

JM: I’ve always been connected to the outdoors. When the opportunity presented itself to come to INHF, it was very natural. I met with Mark Ackelson and he invited me in, there was this land stewardship position open. Quite honestly, I didn’t know a lot about INHF that day, but I really liked Mark, and the idea of working for Mark was exciting. I quickly learned how important the work was, and how much they had already influenced. They influenced a lot of the places I already enjoyed, like the Skunk River Greenbelt.

MA: We had a lot of volunteers, but no program to recognize them and focus the work. We also put more emphasis on our intern program and expanded it into stewardship.

JM: The land stewardship program at that time was a lot different than it is today. I was the only land stewardship employee. We had historically only been more interested in protecting and making lands public, and the idea of owning and managing our own land was relatively new. We had been around for a long time, but it wasn’t necessarily embraced. I felt a real connection to the land stewardship program back in 1999 when I started, and was excited about being able to grow that program.

MA: So INHF is 40 years old and we’ve only had three presidents. That’s pretty remarkable for any organization. That stability is one of the reasons INHF has been successful.

JM: Growing up with INHF — I’ve spent 20 years of my career here — I can’t imagine being anywhere else. I think the beauty of INHF is that the mission has stayed the same. Our commitment to Iowa is steadfast. Our culture has stayed strong. We have had to be creative. The landscape around us has changed. How we do our work — we have had to stay innovative. The most important part is that we don’t let up. We know there is a lot of work to do, and we’re going to face challenges. Many times, there is unnatural opposition, and it doesn’t make sense to us. We need to understand why. That will likely open opportunities to protect even more, and we can come to some understandings of why nature is important to everyone.