Working lands in working hands

By Brianne Sanchez, Volunteer Contributor on April 9, 2024 in Blog

When brothers Dennis and Stephen McLaughlin reminisce about growing up as “farm kids” in Madison County, many of their memories are tied to chores. Countless hours of their childhoods involved gathering eggs, walking beans, podding peas from the big garden, milking the cow and raising cattle and hogs “farrow to finish” among acres of corn.

“Then there was the time we were baling hay and got rained out,” Dennis recalls. “We all took shelter in the driveway of the double corn crib. That is, until lightning struck the windmill just 20 feet away. I never knew my grandpa could run that fast, but we all hightailed it to the house!”

“We spent quite a bit of time with grandpa,” Sharon, one of the sisters, remembers. “Exploring the farm, walking the creek… grandpa got in big trouble with mom once when he let us play in the mud and we came home covered head to toe!”

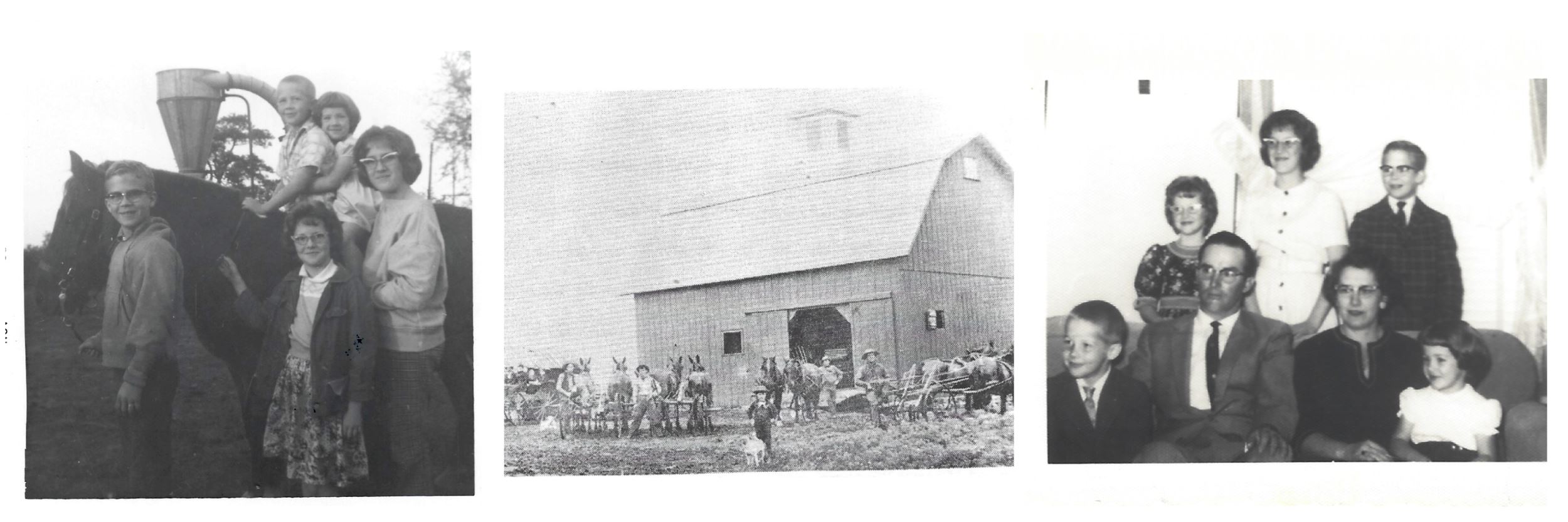

Left and right photos: The McLaughlin siblings pictured with a horse on their farm and then with their parents. Center: This barn still stands at the McLaughlin farm today. Charles McLaughlin, grandfather of the five McLaughlin siblings, is pictured with his dog in the foreground.

Farm life shaped all five McLaughlin siblings, but Dennis was the one interested in making a living on the land. He stayed in Iowa and helped his parents, Lewis and Margaret, weather the Farm Crisis of the 1980s. It was a time when some of their neighbors were forced to sell.

“We’ve just focused on the home place, 320 acres, and tried to make it farm better—not bigger,” Dennis says. “A lot of it was substituting labor for capital. That wasn’t always fun, but that’s what got the bills paid.”

A longtime member of Practical Farmers of Iowa, Dennis continues to advance his parents’ land ethic by investing his efforts into regenerative practices. Preserving grasslands and habitat on the property also benefits the greater Badger Creek watershed and maintains open space.

“Dad was an early adopter of conservation in cooperation with the NRCS (Natural Resources Conservation Service) and the FSA (Farm Service Agency),” Dennis says. “Together they built ponds, diversions, contour terraces and seeded waterways. Today’s efforts focus on improving soil biology which will in turn improve water filtration rates, water holding capacity, soil organic carbon and overall soil health scores. Adaptive rotational grazing is practiced on all 320 acres.”

In the decades since the McLaughlin siblings and their Madison County classmates would hop off the school bus and head into the fields, much has changed. Developers are at their doorstep, with new subdivisions popping up at the edges of the property and a nearby data center converting cropland into developed spaces. Family members were concerned that, as surrounding communities expanded, their farm would be lost. The threat to agricultural production and wildlife habitat would be significant.

In the decades since the McLaughlin siblings and their Madison County classmates would hop off the school bus and head into the fields, much has changed. Developers are at their doorstep, with new subdivisions popping up at the edges of the property and a nearby data center converting cropland into developed spaces. Family members were concerned that, as surrounding communities expanded, their farm would be lost. The threat to agricultural production and wildlife habitat would be significant.

Finding a preservation partner

Holding onto the farm, which was first conveyed to John and Mary McLaughlin in 1854, has required five generations of familial commitment. With Dennis eyeing retirement, and no successor interested in running farming operations, the family needed to come up with a plan for the property. They formed an LLC in 2008, to collectively consider their options and ensure the continued stewardship of the land.

“Everybody understood that we had to educate ourselves,” Dennis says. “Part of the formation of the LLC incorporated the possibility of eventually working with a land trust. We decided it might be a good fit, if it meant that we did everything we could to preserve the agricultural land and natural resources.”

The McLaughlins researched organizations with expertise in land easements, in search of a potential partner. Eventually, they connected with Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation and in 2016 began working with Erin Van Waus, INHF Conservation Easement Director. Her work involves helping the family navigate the legal aspects, ecological elements and the relationship dynamics associated with complex land protection decisions. She’s facilitated more than 70 conservation easements in her tenure, on completion timelines that range from within a year to occasionally spanning decades.

“Oftentimes landowners contact INHF because they want the peace of mind knowing their work won’t be undone and the trees, pastures and open fields will remain beyond their ownership,” Van Waus says. “Protection may be triggered by nearby land uses, estate planning or sometimes in advance of selling the property.”

For those with working lands, Agricultural Land Easements (ALEs) may be the best way to protect beloved pastures and fields. In ALEs, the NRCS provides a payment for 50% of the easement value, and the remaining 50% of the easement value can be offset by state and federal tax benefits.

“ALEs are the best financial option for landowners interested in preserving working lands with an easement,” Van Waus says. “You have to also be interested in preserving conservation and understand all of the stacked benefits. It also protects a way of life, by not squeezing farmers out of this area of high development.”

“For us, it felt like the right decision. We’re only here for a short time, filling in the gap between who was here before and who will come next,” Dennis says. “This land has a long history, and the ALE means it can also have a long future.”

Working close to home

In 2021, INHF was awarded funding through the NRCS for an ALE to protect 107 acres of the McLaughlin Farm. As part of the agreement, the McLaughlin Family donated 50 percent of the easement value and agreed to contribute toward the easement monitoring fund, which helps cover the expense of ensuring land use compliance perpetually. It’s an outcome that the McLaughlin siblings could celebrate, after years of collaborative conversations.

“I had already come to the decision that this was the only way to protect the land from the development that was happening all around us,” Sharon says about the family’s choice to do the easement. “I knew it was what Dad and Mom wanted and I know they are very happy that we made it happen.”

“When doing an easement by committee you have to allow more time for discussions and decision making, but it’s also so rich and gratifying,” Van Waus says. “The process for the agricultural land easement is lengthy compared to donated conservation easements because funding from the federal government is involved. The McLaughlin family was committed to see the land protection through and we were able to finalize the easement in 2023.”

Their ALE still allows for activities the McLaughlins value, including sustainable grazing, row cropping in designated areas and fruit, nut and vegetable production. But it also protects against activities like development, mining or subdividing. The farm’s perennial vegetation, woodland and small stream will collectively provide for sustainable farming practices, clean water and wildlife habitat.

“When you look at the aerial view of the farm, it’s unique,” Van Waus says. “There are a bunch of different colors and patterns indicating diverse crop rotations and conservation practices. It’s exciting to see this much diversity on a farm.”

A birds-eye-view shows the diversity of crops and cover planted on the farm.

Working on the McLaughlin’s easement was especially meaningful for Van Waus because the property is located close to her home, in the same school district her children attend. In the seven years it took to finalize the conservation easement, she’s seen her young sons grow up alongside the grasslands. Van Waus brought her husband and kids along for field studies to help identify birds, trees and other plants for documentation purposes.

“Easements like this one are a great way for INHF to continue to fulfill our mission through private land protection,” Van Waus says. “Wildlife and water quality don’t care who owns the land. It just matters that it’s protected.”